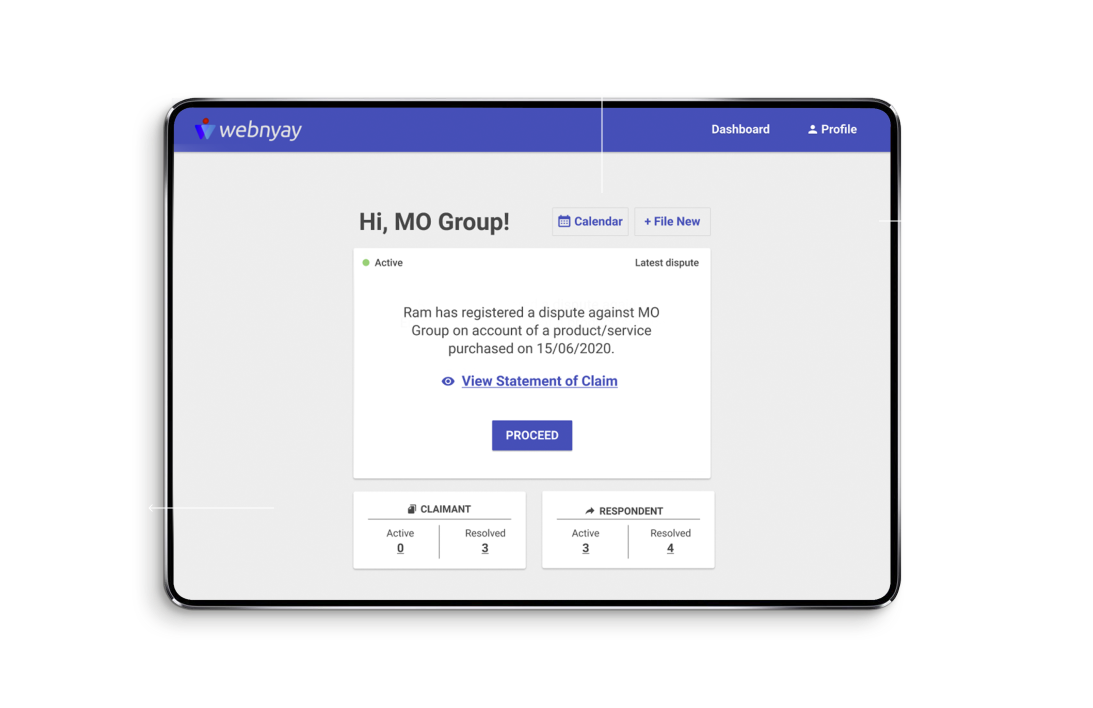

Resolve complaints and disputes outside court

Webnyay is a sophisticated online dispute resolution ecosystem.

We provide an end to end digital platform for resolution of complaints and disputes in an efficient, speedy, flexible and inexpensive manner.

Our vision

Our vision is to provide access to justice for everyone. We seek to empower you to be able to resolve your issues from the very comfort of your home - all you need is an internet connection and a smartphone or computer!

Our products

Webnyay provides everything that is required to resolve disputes in one place without having to go anywhere. Our success is attributed to our rigorous protocols, security, uncompromised quality and our commitment to delivering an excellent service. We have the following service offerings:

CDR - Commercial Dispute Resolution

This is an innovative and technologically advanced service that seeks to resolve B2B, B2C and C2C complaints, conflicts and disputes. It is a one-stop shop for enterprises looking to resolve civil and commercial disputes (including consumer complaints) and grievances from employees, suppliers and distributors. Our sophisticated document automation technology allows users to generate legal pleadings by simply answering questions and uploading documents (and without having to engage lawyers).

We work with experienced professionals (which includes former judges, ombudsmen, senior advocates, queen's counsel, lawyers and domain experts) that act as neutrals on the disputes. We use Artificial Intelligence in our legal and automation processes to ensure that disputes are resolved efficiently and inexpensively.

RV - Resolve Virtually

This is a state-of-the-art platform that can be used to resolve conflicts and disputes online. It is a plug-and-play technology system that can be used by anybody to resolve conflicts and disputes in a secure and seamless manner. In layman terms, this platform "digitises" dispute resolution (ie, offline to online) and enables all stakeholders to resolve differences online. It is ideal for conducting court hearings, arbitrations, mediations, conciliations, Lok adalats, adjudications, grievance and ombudsman redressals, etc.

Institutional Offering

When selected by the parties, Webnyay acts as a neutral and independent arbitration institution that provides secretarial services. We see ourselves as a new-age arbitration institute catering to domestic and cross-border arbitration disputes. We are an online-first and technology-first institution that not only provides world class case management and administrative services but also an online platform for managing and conducting the arbitration proceedings.

Our partners